I am now working with Chronogram’s The River as an investigative reporter.

In Yes In My Backyard, I explore the affordable housing crisis in New York and elsewhere, and how accessory dwelling units could help:

The lack of affordable housing is a huge threat to American society and economy. Conservative estimates suggest the country needs nearly seven million single-family housing units due to a 20-year period of underbuilding, and a gap economists estimate costs the economy at least 2 percent of the US GDP each year. Those who are most likely to bear the consequences are low- and moderate-income folks, who wind up in poorer neighborhoods with fewer social services, lower quality education, and higher crime, and subject to higher pollution, longer commutes, and other health risks.

As the flooding of basement apartments in New York City this summer demonstrated, affordable housing is also a climate equity issue. Many basement apartments in the city are illegal—they don’t meet the requirements for light, air, sanitation, and exits—and lack features that would make them safer as a result.

Basement apartments are one form of accessory dwelling unit (ADUs), which also include “granny flats,” in-law apartments, converted garages, casitas, and other forms of infill housing added to single-family properties. ADUs can be an affordable rental option, since they are generally small and often repurpose existing space. Their construction can be done at lower cost than other housing options, since the owner already has title to the land. That makes it quicker to develop ADUs compared to other forms of affordable housing, like multifamily homes underwritten by government or philanthropic funding, or inclusive zoning, where a developer agrees to rent a certain percentage of units in a new development at affordable rates. Owners may have a financial motivation to create an ADU for rental income, or as housing for a family member, once zoning barriers are removed.

The Hudson Valley region forms a microcosm within the national housing crisis: all the pressures affecting affordable housing elsewhere are present here. We’ve seen the influx of new residents moving from urban centers because of the pandemic, for example, and the rising prices that started even before COVID-19 have only accelerated.

The same barriers to countering the housing crisis exist here, as well. In other parts of the country, state legislatures, such as Oregon, have passed new laws that directly attack residential zoning, which more than any other factor has slowed the building of new housing where people want to live and work. Bills have been introduced in the New York State Senate and Assembly that propose a top-down overhaul of zoning regulations, in essence standardizing zoning ordinances across the state that relate to ADUs and removing many of the prerogatives of municipal zoning boards that historically have blocked higher density developments in general, and ADUs specifically.

But so far, New York has refused to act.

Anyone interested in housing policy, zoning issues, and the history of real estate inequity will find this of interest.

One pull quote:

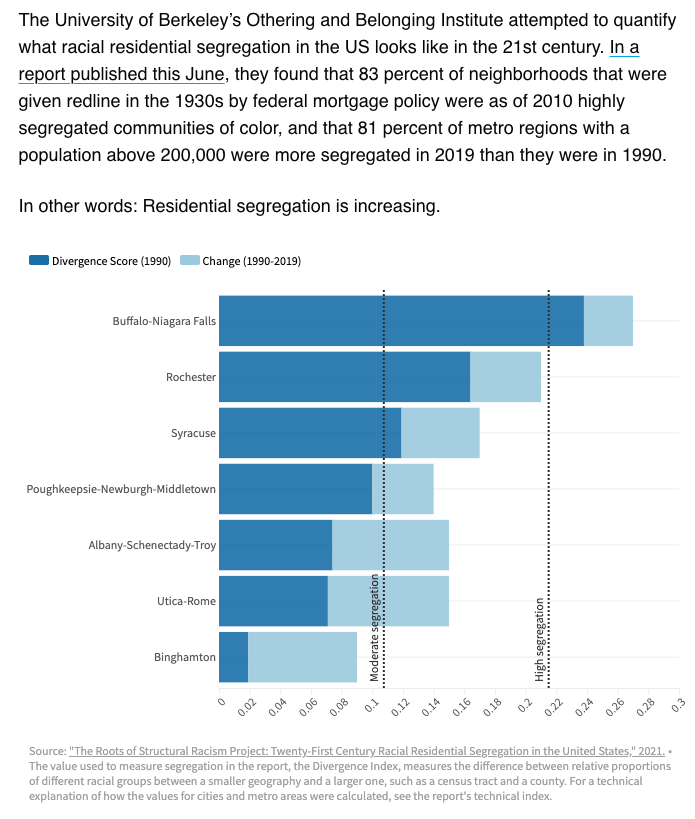

The residential caste system is maintained today by zoning regulations, rather than the explicit conspiracy of redlining between banks, real estate businesses, and governments. But the effect is the same.