The "New New York"

Gov Hochul and Mayor Adams released a report: Making New York Work For Everyone

In Hochul and Adams Envision ‘New New York.’ Getting There Is the Trick., Jeffrey Mays and Nicole Hong report on a recent press conference, in which the Governor and the Mayor spoke about the future of New York City and the region:

Gov. Kathy Hochul and mayor Eric Adams unveiled a reimagined vision for a “New New York” Wednesday, while acknowledging that the pandemic has fundamentally changed New York City.

The plan, titled “New New York: Making New York Work For Everyone,” suggested that reinvigorating the city’s commercial districts by transforming them into 24 hour live-and-work spaces was key to the city’s future.

The ‘24-hour live-and-work spaces’ theme is only one aspect of a staggeringly long and dense report but is the sort of sound bite that catches the attention, more than the many pages dedicated to rezoning, details about various business districts, what sorts of advanced manufacturing should be sought, and the need for better childcare, as just a few examples.

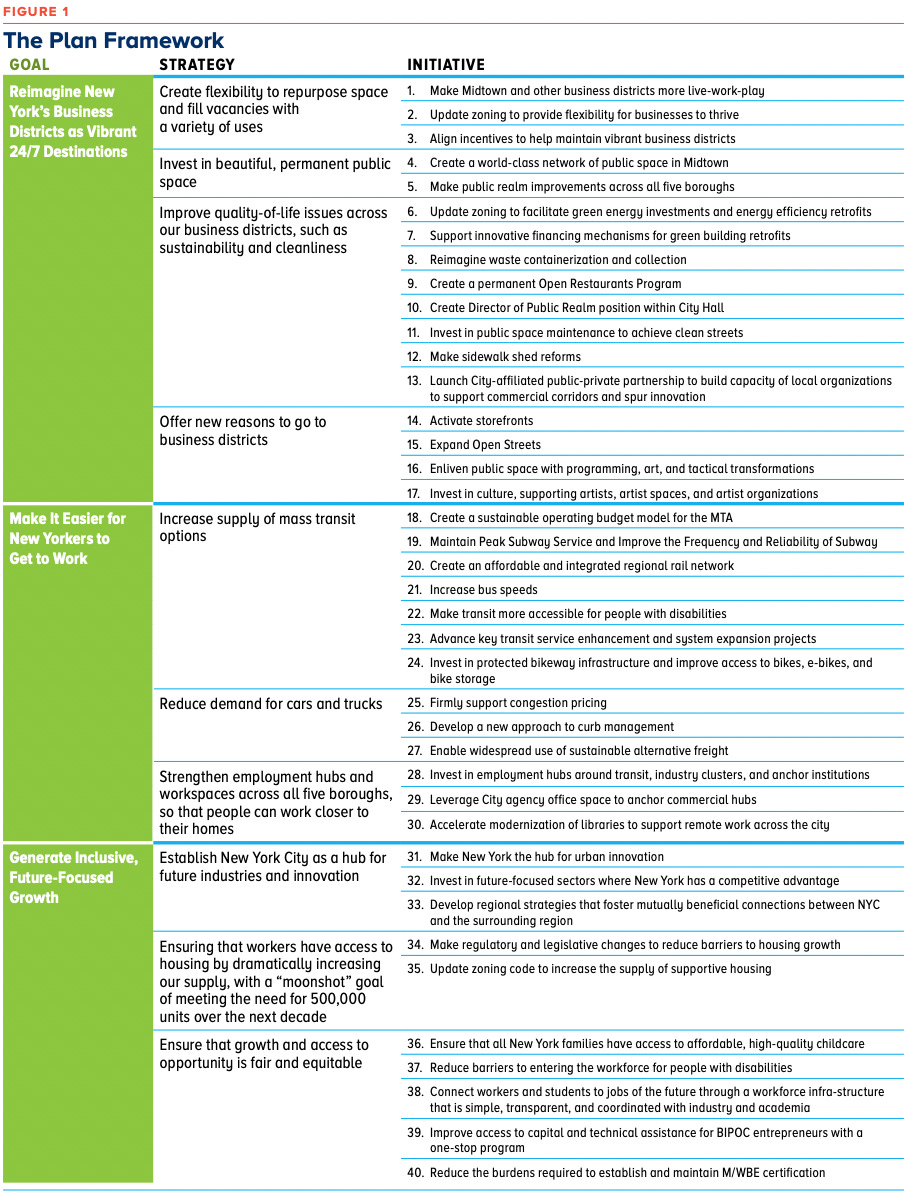

The Plan has three major goals, the first being ‘Reimagine New York’s Business Districts as Vibrant 24/7 Destinations’, with four strategies leading to 17 initiatives. The other two goals are ‘Make It Easier for New Yorkers to Get to Work’ and ‘Generate Inclusive, Future-Focused Growth’.

In my view — and I have only read through the report once and quickly — the three goals can be thought of as having near-, medium-, and long-term life horizons, and the real payoff will come in the third.

Establish New York City as a hub for future industries and innovation — The report identifies a variety of industries that would potentially replace the office workers who have fled the city as companies have accepted remote work as their new mantra. Instead of workers typing on laptops, the city wants to attract industries where the workers need to show up, like biotech, advanced and green manufacturing. It would also be smart to attract more educational institutions to create NYC hubs (or move there altogether) repurposing empty office space for classrooms, libraries, labs, and dorms.

Ensuring that workers have access to housing by dramatically increasing our supply, with a “moonshot” goal of meeting the need for 500,000 units over the next decade — I think you are dooming yourself by calling a goal a moonshot (although the last time around we did get to the moon), but clearly housing is in a crisis, and creating more of it will lead to a reduction in prices. If the City is to attract skilled manufacturing workers for the new industries, there will have to be more affordable housing.

Ensure that growth and access to opportunity are fair and equitable — One standout is an initiative toward affordable, high-quality childcare.

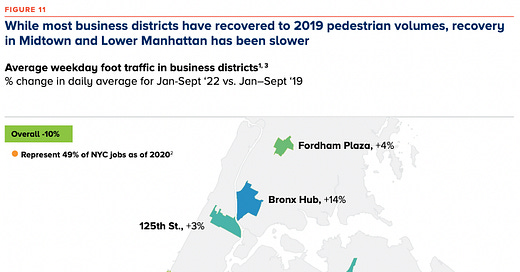

The report focuses on some trends that can be built on. Some business districts are seeing higher foot traffic now than in 2019, but Lower, South Midtown, and Midtown Manhattan are suffering the most:

Long Island City, Forest Hills, and Broadway Junction are considerably busier now than prepandemic. Presumably, because people aren’t traveling to Manhattan to work in those office towers. This is immensely important to the City since much of the tax revenue has come from Manhattan:

Why should New Yorkers across all five boroughs care if Midtown and Lower Manhattan are struggling, especially if they’ve seen their own local commercial corridors rebound and even thrive in the last year? Because even if an individual’s job is located somewhere else, Manhattan’s business districts are New York City’s hubs for global business dominance, generating 58.5 percent of the City’s office and retail property tax revenues and 18 percent of over-all citywide property tax revenue. This tax base powers the government spending on physical and social infrastructure that touches every New Yorker, whether it’s paving roads, providing public education, or running senior centers and libraries. Simply put, we must stabilize our Manhattan business districts so that we can continue to invest throughout the five boroughs.

The significance of Midtown and Lower Manhattan resonates beyond the city. Before the pandemic, Manhattan welcomed 664,000 regional commuters per day on average—the majority in Midtown, Midtown South, and Lower Manhattan. 200 These commuters, if they work from home, may spend their dollars in other states. Meanwhile, international business travelers rely on a central, convenient destination for meetings to make their trips worthwhile. Companies chose to locate in Midtown because they knew it would position them to compete globally, offer access to a concentration of industries across sectors, and attract workers from around the world.

The city’s infrastructure has been designed to support this influx of workers, with a combined 28 subway service lines, 25 commuter rail lines, 11 ferry routes, a dense bus network, and a robust Citibike system with over 1,500 stations. Much of this infrastructure is designed to connect people to the city’s Core Employment Hubs, which also makes them the most sustainable places to focus our commercial density.

Over the years, the extraordinary commercial concentration in Midtown and Lower Manhattan have generated abundant returns, fueling an ecosystem that supports the most far-flung business travelers and the local owners of a corner deli, while producing revenues to fund services across the entire city. That’s why, before the pandemic, when workers were simply required to show up in Manhattan’s business districts every day (and did), we could gloss over an inconvenient fact: a lot of people don’t really like it there. Now that workers have more choices, an overwhelming number—still more than 50 percent—are deciding not to make the daily trek into the office. The sleek but anonymous streets that empty out every night and weekend lack the life, interest, energy, and beauty that brought many to New York in the first place. In this new world of choice for many employers and businesses, we need to entice people to come by creating a place they want to be.

That means we cannot simply revive Midtown and our other business districts. We must reimagine them.

The report spends 164 pages attacking that problem from 40 tangents. From my perspective, they range from fanciful to practical, but most importantly, they lack any details about the cost involved. But saving a city that was guestimated at being worth a trillion dollars for real estate, alone, clearly, it’s worth investing many billions to retain the unofficial position as the capital of the Western world.

I plan to take a closer look at initiative 33, ‘Develop regional strategies that foster mutually beneficial connections between NYC and the surrounding region’, to see what might be in the offing for us in Beacon and the surrounding area.

More to follow.